© 2018 Dr Margaret Sheppard

A woman who has just given birth is called a Motsetsi (pl. Batsetsi, condition -

As already noted, even if a woman is married, for her first baby born after her marriage (and even perhaps her second) she will spend her Botsetsi at her own home with her mother or a close female relative, such as a sister or aunt, being responsible for looking after her. There is always a certain woman who is responsible for looking after a Motsetsi and her child. As will be seen most of the taboos and customs surrounding a Motsetsi have the effect of protecting her from arduous work, and aim to protect her and the young baby from infection.

A Motsetsi is not allowed to cook, she is believed to be “dirty” and therefore could contaminate food through her “maoto a molelo'” (hot blood) condition. The woman responsible for looking after her cooks for her and looks after all her things as the motsesti has her own crockery, cooking pots and cutlery, which are kept absolutely separate with no one else being allowed to use them. The only exceptions to this are the other young children of the family who may use them and also eat some of the food that is cooked specially for the Motsetsi. If people who are old enough to have sexual relations were to share these utensils and the Motsetsi's food, it is believed that harm would come to the baby. This would be shown by a swelling of the umbilical cord. In some very traditional homes a separate bucket may be kept for fetching the water for the Motsetsi.

Immediately a Motsetsi is confined in a house, or when she returns from the hospital with her small baby, the house is "closed" by a traditional doctor. Crossed sticks may be put across the entrance or on the ground to symbolise this. He will also apply special medicines to protect the mother and baby from attack by those who may wish them harm, such as through sorcery. These are strong medicines and anyone trying to challenge after their application would become senseless as the intended sorcery would be reflected to them. For the first week or two after birth, entrance to the house where the Motsetsi is confined is severely restricted. This is so until the umbilical cord of the baby drops off, at this time its “birth” hair is also shaved off. The restriction on admission to the house is obviously a sensible one as it helps to protect the baby from infection.

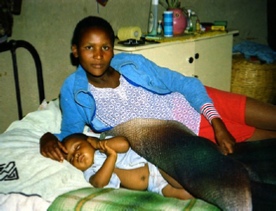

The mother lies usually on her stomach, on her blankets on the floor, with her baby beside her. Lying on the stomach is supposed to help the stretched stomach muscles to return to their former natural shape. The baby suckles frequently on demand at its mother's breast. The mother herself is fed frequently on large bowls of matogo (a soft thin porridge made from sorghum or maize meal), milk, tea, meat and vegetables. Each time she eats, her hands are cleaned for her by the woman in charge of her Botsetsi, and her food is dished into her special plates. These are always washed separately and the water used is tipped away well inside the yard to protect against sorcery.

She lies on her stomach to eat and drink, again this is believed to help her stomach muscles. While she is eating someone else will hold her baby, this cannot be the woman who is dishing her food for her, nor must this woman touch her blankets while serving the mother, as this again is believed to contaminate the food.

At the beginning of the Botsetsi the woman in charge of the Botsetsi would have given all the rules to the other members of the household to avoid mistakes.

ndant takes the child outside and as she shows it the new moon,

she says, "There is your mate. Look at him. Kur r r ru."

Then when the baby wriggles and opens its eyes, the other adults present

(all close relatives) say,"He has seen it." The child is then taken

. . d *4

1nS1 e.

The mother and the child continue in seclusion for up to 6

months. Several of the Batsetsi I knew spent 4 or 5 months in seclusion,

particularly if it was a first baby and they were not working. As a

Motsetsi becomes stronger, although she continues to wrap herself in a

*1 Pauw op. cit. page 14-

*2 Schapera op.cit. page 212.

*3 Schapera op.cit. page 211-

*4 Setiloane op.cit. Page 176.

160

blanket and tie her scarf around her cheeks under the chin, and does not

greet nor is greeted by passers-

lighter tasks in the lolwapa. She may wash hers and the baby's

clothes (it is in fact a taboo for the napkins of a baby to be washed

by anyone except its mother, the attendant, or a very close relative,

this is because this can be a way of bewitching the baby, through its

faeces. The water used to wash these things and the mother's clothes

is poured well inside the lolwapa to avoid it being taken by baloi.)

A Motsetsi cannot cook food or fetch water. Until the seclusion ~s

over, her food will be specially cooked for her by her attendant who will

also wash her hands for her before she eats. If for some reason her hands

cannot be washed the food will be put straight into her mouth for he~ or

her cup will be held for her while she drinks. Should she visit a

nearby house (without the baby, who does not go out) she will not eat

there. If she did, she will have to be fed by hand, and if she uses any

utensils, for example, cups, spoons, plates etc., because of the taboo

against sharing the uten%ils of a Motsetsi, the Motsetsi must be given

these things to take away with her.*l Not to follow this taboo could

lead to possible harm to the baby if the utensils were subsequently used

by a person who is sleeping with members of the opposite sex.

At the end of the period of seclusion the mother and baby should

have both grown fat, and are also usually very light-

much of the day inside, both of these attributes are considered very

beautiful. A day is chosen and a feast usually called a Botsetsi party*2

is held. The walls of the malwapa in the yard will have been newly

decorated with coloured muds. Traditional sorghum beer is brewed, and a

beast is slaughtered for the mother and baby (in rich families it might

even be a bovine beast), salads, samp, rice etc., are cooked. The

maternal and paternal relatives of the baby are invited, also friends

and neighbours. On this day the mother and baby are cleansed and

doctored by being ritually washed by a traditional doctor. The mother

and baby are both dressed in smart new clothes bought by the baby's

father. Both the mother and baby are on show to, and much praised by,

all those present, and the baby is passed around for admiration.

*) On two occasions I gave refreshments to visiting Batsetsi and

to give them the cups, plates and spoons they had used. They

had to be fed by another person.

Setiloane, Schapera and Pauw all refer to this occasion as ~

ntsha ngwana motlung -

had

also

*2

161

Guests give presents to the mother and baby. These gifts are all

carefully recorded by a person chosen to be responsible during the

Botsetsi Party for receiving and recording the gifts and donors 1n a

notebook. These gifts commonly consist of money (St to several pula),

glassware, crockery or baby clothes.

Men are as customary, responsible for slaughtering and cooking

the meat. This they do in the kraal of the family kgotla. The female

relatives brew the beer and prepare the rest of the food. Women usually

also serve the guests with the plates of food already dished out.

"Important" guests are seated at tables, and others will sit On the

ground and eat around the 101wapa and yard. The "most important"

are given the "full menu", but even casual passers-

served with whatever is available such as fat cakes (a kind of doughnut)

or samp (crushed maize) or sorghum or maize porridge. As with all

feasts, Badimo (the ancestors) are believed to be present. They are

believed to be attracted by the spilling of blood when the beast was

slaughtered, as they like c.Pmpany and rejoicing, this may also be seen

as a feast to thank the Badimo for looking after the mother and baby

during the dangerous first months of the baby's life, and protecting

the mother and baby from harm.

On this day there is much rejoicing, and as people become merry

with beer there may even be singing and dancing. From this day the

baby is known by its name. Traditionally the maternal relatives would

call it by a name chosen by them and the paternal relatives by their

chosen name. Most Tswana names have meanings, and children are commonly

named after ancestors or important events, or as thanks, or as a wish

for success for a child in its future life.*1

From this day onwards, the mother nOw resumes her normal duties,

but continues to avoid at first the heavier kind of household work, such

as heavy digging. If a married mother and baby were being secluded at

the maternal home, then usually about a week after the Botsetsi Party

she will be returned with the baby, by her parents, to her husband's

home. Traditionally they would be taken there by ox wagon or donkey

*1 Examples of common names: Mmatlalepula -

(for a child born during the Rain), Kelebogile -

I have forgotten (e.g. if there had been a family death or misfortune

before the child's birth), Ofentse -

born at the end of the war etc), Khumoetsile -

the sense of a girl who will hopefully bring bridewealth).

162

cart, the mother and baby being dressed in their best clothes, and of

course ideally they should both look fat and light-

arrival, they will be served with food, and probably traditional beer

will also have been brewed. This is in gratitude to the baby's

maternal relatives for caring for it and its mother.

Letlhomela Child -

Th ' f 1, .. h d . *1

e 1.n ant morta 1.ty rate 1.S h1.g compare w1.th the Wes t .

When a baby dies it is obviously a very sad event. The associated customs

and taboos will be described later in the section on Death and Funerals

in Chapter 8, but here the customs and beliefs relating to the next child

born after the one who dies should be noted.

Such a child is called a Letlhomela~2 this means an offshoot

or graft. It is often very much feared that such a child will also

follow the one before to the world of the Spirits. According to

Setiloane it is these children who are shown the new moon the first

time it appears after their birth.*3 The baby is treated very carefully

and under the direction of a tra~ional doctor, its Malome may dress it

in little skunk skins which will include a little skin purse. Every

time a visitor touches such a child they will put a little gift in its

purse, such as a small coin, snuff, tea etc., as these children are

believed to be very poor. The child will wear these skins under its

ordinary baby clothes and they will not be removed until the traditional

doctor orders (maybe when the child is 3 or 4 years old or the clothes

grow too old and fall apart). If the child manages to survive the

period of seclusion, it will be given a name that means something poor

or useless, for example Serurubele (butterfly), Mokgalagadi (the tribe

from the West, after the Setswana saying "as poor as a Mokgalagadi"),

or Phokojane -

to place). According to Setswana tradition, a bad name is thought to be

a curse, so the idea here is that the family want to show they have

already been cursed enough (i.e. by losing the previous children) so

this is like a prayer to their Badimo to protect this child and allow

it to live.

In 1980 I observed another way in which a Letlhomela child may

be treated. One child who came to visit the family I was staying with

*1 E.g. in 1979, 20,872 births were recorded in hospitals, of which

20,154 were discharged alive, i.e. a death rate of 3.4%. See section on

"Modern" Health Services in Chapter 1 for fuller details.

*2 Setiloane page 176

*3 See page 159 of this section.,

Botsetsi - The confinement of the mother and her child

When visitors come, especially for the first time. they will usually bring a small gift for the mother such as candles, soap, coffee, sugar, sweets, wood, or may help to fetch water for the Motsetsi. The baby as yet does not officially have a name and is usually referred to as "the child". The mother usually wears a head scarf tied around her head (as in English fashion), this is to hide her cheeks. Whenever she goes out of her house she will wrap herself in a blanket. If a passer-

The motsetsi has a screened off area in the house, only children or the woman taking care of her will sleep in this house. No one who has “hot blood” will enter the house as this could harm the baby i.e. the newly bereaved, those who have had recent miscarriages etc.

The father may well send a load of wood for cooking fire for his wife and child

As the baby grows older the Motsetsi may start to visit neighbours houses. If she does, she is “fed” by the woman taking care of her and any utensils she uses at this house must be given to her to take away or smashed. No one else must use them after her. This would harm the child.

During this whole period she is considered "dirty". Just as no one should eat from her dishes, so she should not use those of anyone else, or they will become senseless, i.e. her condition can weaken their seriti (shadow). The father of the baby is not supposed to sleep with any other woman or the baby's umbilical cord will start to protrude and may even burst, and the child will not grow properly.

The paternal relatives of the child may slaughter a sheep or a calf for the mother of the baby. Before woollen blankets became fashionable the skin of this beast was used to make the baby's first "cradle-

The mother and the child continue in seclusion for up to 6 months. Several of the Batsetsi I knew spent 4 or 5 months in seclusion, particularly if it was a first baby and they were not working. As a Motsetsi becomes stronger, although she continues to wrap herself in a blanket and tie her scarf around her cheeks under the chin, and does not greet nor is greeted by passers-

A Motsetsi cannot cook food or fetch water. Until the seclusion is over, her food will be specially cooked for her by her attendant who will also wash her hands for her before she eats. If for some reason her hands cannot be washed the food will be put straight into her mouth for her or her cup will be held for her while she drinks. Should she visit a nearby house (without the baby, who does not go out) she will not eat there. If she did, she will have to be fed by hand, and if she uses any utensils, for example, cups, spoons, plates etc., because of the taboo against sharing the utensils of a Motsetsi, the Motsetsi must be given these things to take away with her. Not to follow this taboo could lead to possible harm to the baby if the utensils were subsequently used by a person who is sleeping with members of the opposite sex.

The mother and baby typically will lie on the floor of the house

The mother is given matego (soft porridge which she will eat lying on her stomach as this helps the stomach muscles to return to their normal position

Her utensils are kept separately and not used by anyone else as this could harm the baby

7 days after birth the baby’s first hair is shaved off and carefully disposed of so that would be sorcerers cannot access it using it to harm the baby and mother

Various traditional medicines -

When a baby is born its birth is announced to all the maternal and paternal relatives. who will come to inquire after the mother and baby. After the first week or two, when the umbilical cord has dropped off, they are allowed to visit the mother and baby. especially the women, so long as they are not suffering from "hot blood". "Hot blood" is caused by menstruation or a close contact with a death.

If it is the ploughing season and the Motsetsi and baby are strong enough, they may well be taken to the Lands. A cow and/or goat may be brought from the Cattle post to ensure the mother has plenty of milk. This enables her mother or the woman caring for her to also undertake their important work at the Lands -